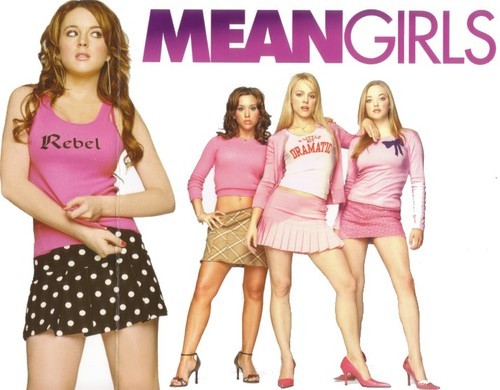

Mean Girls has become a pop cultural phenomenon of memetic proportions. Even people who have never seen the movie can quote from it at length. Considering that the movie is female-centric and tackles issues like girl hate and body image, many people hail Mean Girls as feminist, and it’s clear that the screenplay writer, Tina Fey, intended it be so as the protagonist “Cady” is named after suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton. But in my opinion, Mean Girls is not actually very feminist. Don’t get me wrong: the movie is obviously incredibly well-done. I think it’s super clever satire, and there’s positive aspects for girls in the movie, but I enjoyed it as a well-written, entertaining film—not as a feminist one, for various reasons.

This post is first in my series of feminist reviews of media. See here for details on my ratings system and criteria.

Everyone who hasn’t seen this movie probably knows what happens through gifs alone, but obligatory spoiler warning.

Mean Girls centers on protagonist Cady, who has been homeschooled all her life and is completely new to the social dynamics of high school. Two outsiders, Damian and Janis, take her under their wing, but when the Plastics, the prettiest and most popular girls in the school, vie for her attention, she is sent in as a mole by Janis to infiltrate the Plastics and undermine Queen Bee Regina George’s cruel reign. Throughout the movie, Cady winds up becoming something of a Mean Girl herself, blowing off her friends and becoming enamored with the Plastic lifestyle. The girls, especially Regina, manipulate, insult and bully each other. The film’s resolution comes after the contents of the Burn Book, where the Plastics write all the school gossip, are revealed to the whole school, and when all the girls in the school are forced to resolve their conflicts.

Women: 6/10

Mean Girls‘ strengths lie in its girl-centricism and how it encourages girls to rise above attacking each other or downplaying their own abilities for men. The movie delivers these messages in a comedic way through the development of its protagonist and other central characters. But while the girls eventually learn to support each other and stop bullying each other, the actual problems in society that cause girls to act this way are never explored. The film makes it look like teenage girls act this way just because and only need a kumbaya session to get over it. And while the girls are more developed than the boys and take center stage, most of them are stereotypes. The Plastics are a trio of caricatures: the dumb blonde (Karen), the Jewish American Princess (Gretchen), and the backstabbing popular girl (Regina), but even the other main female characters, who are portrayed more positively, don’t escape this fate: such as Cady’s friend Janis, the snarky, eccentric lesbian and Tina Fey’s character, Ms. Norbury, the pitiful spinster, and most of the side characters are little more than whatever clique they belong to (band geek or Asian mathlete).

Cady, the protagonist, is the most developed character with a multifaceted personality. Unlike everyone else, she does’t fit easily into stereotype, but she is a white homeschooled girl from “Africa” with a complete, unrealistic ignorance around American culture and teenaged socialization. She seems to come from another dimension where there’s no such thing as “society.” Thus, the person who cures Girl Hate in the movie is a mythical figure who doesn’t exist in real life: someone introduced to the beauty industry and internalized misogyny at the age of 16. It’s no accident Cady isn’t a popular girl who learns the error of her ways. Or, heaven forbid, a popular girl into fashion who isn’t mean. Nor is she a nerdy girl grappling with her social standing. She is a magical Outsider immune to all this stereotyping in the first place, moving between nerd and popular girl, while everyone else fixedly adheres to stereotype, allowing the film to side-step truly challenging stereotypes or addressing the sources of internalized misogyny altogether.

Why do the girls put down their own appearance and that of other girls? Why are they so mean to each other? The movie never tries to parse this out. The male characters in the movie are peripheral, which is both good and bad: good in that girls are the center of the movie, bad because the main source of misogyny in the film is girls themselves. In fact, men and boys are rarely shown being sexist whatsoever, and when they are, it’s a joke or minor plot device. Unlike Legally Blonde, which depicts women working together to confront misogyny from men and society, Mean Girls presents misogyny as a girl problem. It’s not that boys like Aaron, Cady’s love interest, are intimidated or turned off by girls like Cady being good at math, it’s that girls like Cady just dumb themselves down to have an excuse to talk to these boys. It’s not that our society has a vicious beauty industry that literally pressures girls into starving themselves, it’s that a few popular girls decided that being thin is important and so they take dangerous drugs to get skinny, which is funny somehow. Men can sit through Mean Girls, content in the knowledge that girls are just catty and mean, so misogyny is their problem to fix. But the film doesn’t even offer girls any real tools to address internalized misogyny!

The movie is definitely far from wholly negative, though. It’s important that the movie ends happily, with Queen Bee Regina not remaining demonized, but finding a suitable outlet for her anger (sports), and girl hate being overcome (even if the “solution” in the movie isn’t applicable to real life). It’s also wonderful to see the gender roles reversed with heartthrob Aaron being nothing but a tool to Regina and a vapid male bimbo with no real traits other than being incredibly attractive and kind but bumbling, and the other white boys, like Regina’s jock boyfriend and Gretchen’s love interest, being similarly vapid. It’s also true that the movie is lacking the outright misogyny intrinsic to so many Hollywood films and replaces it with girl power—but all of it is incredibly superficial and in place of what could be a much more feminist narrative.

PoC: 4/10

Throughout the movie, many PoC are visible in the background and make brief appearances in small roles. They have one-liners like “I’m from Michigan” from a token Black girl who is assumed by the teacher to be from Africa, when Cady actually is (which in and of itself is racist—what country or city in Africa is Cady from? And why is Africa treated like a savage wilderness when there are cities there?). PoC serve mostly as background decoration behind a white central cast, and, unfortunately, are at times reduced to stereotype. There’s even a scene where Cady’s friend Janis points to different cafeteria tables pointing out “the nerdy Asians,” “the cool Asians” and the “unfriendly Black hotties.” Most troubling is the portrayal of the Asian girls in the movie, who are shown only speaking Korean and being completely isolated from the social world of the rest of the school and continue to be “queen bee types” even after the rest of the girls have improved. Worse, the school coach making out with two of these Asian girls is made into a joke, playing into the racist notion that Asian girls are more “grown up” and sexual.

One of the very few prominent PoC characters is Kevin, the overbearing South Asian mathlete who appropriates AAVE and hits on women. I would say Kevin’s portrayal is mixed: he’s funny and not exactly a complete stereotype but also offensive in his sexism and Black appropriation. Most of the white boys in the film are benign and passive, but Kevin is pushy and sexist throughout the movie, though it’s played for laughs. The school principal Mr. Duvall, a Black man, is probably the best PoC representation in the film. He defies stereotype as occasionally stern but never unkind and is neither hypersexualized or desexualized, shown displaying a romantic interest in Tina Fey’s character in a charmingly awkward way. There is one point when he shouts: “Aw, hell no. I didn’t leave the south side for this!” when the school girls all begin fighting in total pandemonium. This moment is interesting: an educated and well-dressed Black man is briefly revealed to be from a lower class background, but neither his accomplishments nor social standing are undermined, subverting the racist dichotomy between “bad” Black person (or “thug”) and “respectable” Black person in this moment of code switching. He doesn’t get much screen time or development, though.

Janis’ character is technically a WoC (Lebanese) but is played by a white Jewish woman, and we go nearly the entire movie with the assumption she is white until she mentions being Lebanese. Earlier in the film, Kevin, who she winds up in a relationship with, mentions only dating women of color (which is played as a joke somehow?) so it seems they shoe-horned in her being Lebanese last minute for the sake of a punchline. Overall, Mean Girls isn’t racially progressive, as stereotypes are upheld and white faces take the foreground.

Trans people: —

There are no trans people in this film, but there are also no trans jokes as far as I could tell.

Sexual Minorities: 4/10

Although Damian and Janis, Cady’s close friends, are prominent characters, they represent a lot of what is wrong with gay representation in the media. Damian, the large and lovable gay sidekick, has always been a controversial character. His trademark line “too gay to function” is oft-quoted and oft-criticized. Damian is de-sexed and safe. He exists to be fabulous, funny and make cute jabs about fashion. He wants to be one of the girls: he even goes in the girls’ bathroom and is actively part of Girl World, as Cady calls it. The conflation of gender and sexuality is of course problematic. But Damian is overall presented as a likable, good person and friend, and gets a lot of screen time—further, it can’t be denied that feminine gay men like Damian exist. He does, however, only serve a heterosexual plot line and has no sexual or romantic interests of his own. This is a common trope that keeps gay men palatable to straights.

Despite ending up with a boy in the end, Janis is heavily lesbian-coded throughout the movie and continually referred to as a lesbian, which she never denies. Janis claims that saying Damian is “too gay to function” is only ok when she says it, and the reveal of Janis once having a crush on Regina during their friendship in junior high, as well as her insistence on keeping it secret is telling. In my view, she is subjected to the common homophobic trope of Lesbian Living Happily Ever After With a Dude. Further, if you think about it, Janis is arguably the meanest and most manipulative of the girls—she completely uses Cady to get sadistic revenge on Regina, going further than any of the other girls do, and relishes it at the end. Then again, all of this is presented as justified in the film, and she is a prominent character and is funny, witty, insightful and resourceful. But her ending up with a guy is a cop out: some people will interpret her as having been straight all along. All in all, both characters uphold many tired homophobic tropes even while they grant us desperately desired and prominent representation.

Disability: 3.5/10

The two visibly disabled characters in the film—a girl in a wheelchair and a little person—are little more than window-dressing in this movie. They aren’t, thankfully, reduced to jokes or stereotypes and at least present some positive representation. Regina’s use of the R-slur, which is not criticized, although it arguably reflects negatively on her character, also brings down the representation rating. The film also trivializes eating disorders when it jokingly refers to “girls who eat their feelings” and “girls who don’t eat anything” as cliques. The movie does better than most by simply including physically disabled people as just everyday people just living their lives without negative stereotypes, but considering they have bit parts, they are little more than tokens.

Abuse/Assault/Relationships: 6.5/10

Overall, the way relationships are depicted in this film is positive in terms of conflict resolution, apologizing and forgiveness. The girls had very dysfunctional and harmful relationships with each other, but they improve. In fact, most of the adults in the movie, who act as moderators in these conflicts, have healthy relationships with the students. Tina Fey’s character, math teacher Ms. Norbury, serves as a good role model for the girls in the movie, especially Cady. The way she helps the girls make up but also retains her status as an authority figure is healthy: she pushes Cady, expresses disappointment and also encouragement at the right times. Cady’s parents too seem to exemplify this balance well, as peripheral as they are in the movie. They are new to the task of handling a teenage girl in a public school environment, but they take seriously enforcing her being grounded, but also are supportive and care. The bad adult role models are presented negatively—such as Regina George’s mother who tries to be a “cool mom” and a friend to her daughter, wanting to be young again. She allows Regina to do whatever she wants, which is implied to negatively contribute to Regina’s character.

As mentioned before, a deeply troubling aspect of the movie is how the coach making out with two Asian high school girls in the film is made into a joke and glossed over. A school teacher preying on a minor under his care is turned into a punch line—it’s essentially a rape joke. In terms of abuse, Janis is very manipulative, but never portrayed negatively for this. She uses Cady to exact revenge against Regina and when she confesses her actions, she is praised for it. Also, when Cady calls Janis out for her manipulation, Janis only puts the blame back on Cady. There never really is conflict resolution for this, either. There’s also the fact Gretchen retains the same character flaws and remains a mean girl but only in the Korean girl clique, which is presented as a positive resolution somehow. All the romantic relationships took a backseat to female friendships, so I found them to be bland and unremarkable, neither negative nor positive.

Body Image/Body Diversity: 3.5/10

Mean Girls continually depicts teenage girls disparaging their own appearance and insulting and critiquing the appearance of other girls. This is, however, presented in a critical way and by the end of the film, Cady realizes that doing this won’t get her ahead in life. That’s a positive message, but by the same token, the film doesn’t ever unpack why girls do this or the underlying problems of body image. Further, we continually see the main characters of the movie, who have idealized, perfect bodies, putting their own appearance down—this is presented as a silly ritual the girls undergo, but it also is never shown to be as damaging as it is on female self-esteem. Worse, is Regina George’s “weight gain.” At one point in the film, Cady tricks Regina into eating Kalteen bars that will make her gain weight as part of the plan to dethrone her as Queen Bee. I question the need to focus on Regina’s weight in her “take down” whatsoever, as it just reinforces fatphobia, especially since her “weight gain” is quite subtle and the issue of weight is never truly explored.

Damian and some side characters provide some body diversity, but fat characters as a whole, especially the girls, pretty much just provide jokes or punchlines in the movie: the “attractive” characters are all thin. The movie satirizes female obsession with weight and image, encourages girls not to put others down for their appearance and also shows Cady as improving when she compliments other girls on their appearance, but it never actually gets to a real criticism of body image, nor does it ever present fat people as being as attractive as thin people.

Jews: 3.5/10

Blink and you’ll miss it, but Gretchen Wieners is canonically Jewish: as the above gif confirms, she celebrates Hanukkah. Many viewers probably watched Mean Girls and remained unaware of this fact considering this one line is the only indicator of her Jewishness. With the acknowledgment Gretchen is Jewish, however, comes the question of her representation of Jewish women. While Gretchen is much less cruel than Regina (as is Karen, the “dumb blonde” of the trio), she also is perpetually a boot-licker to whoever’s queen bee (something she secretly resents). And she of all the Mean Girls arguably changes the least—remaining unapologetic about her meanness and retaining the same status of mean girl, just within the microcosm of the Korean students.

Some have questioned if Gretchen upholds the Jewish American Princess stereotype—i.e. the idea that Jewish American girls and women are spoiled, monied, neurotic and high-maintenance. As others have pointed out, her wealth is her most notable feature as the daughter of the inventor of toaster strudel. The gif above itself highlights how spoiled she is, same with when she threatens the principal with her father’s status to get out of trouble. Her neurosis is revealed as Cady gets under her false exterior… That said, it’s positive to see a Jewish main character included in a film like this who is also presented as beautiful, but considering that her Jewishness is nearly invisible, that she is played by a non-Jew, possesses stereotypical traits, and exhibits little character development/growth, I can’t say she provides good representation.

Conclusion

In the end, Mean Girls is representative of today’s defanged pop feminism that says women need only “lean in” and change their behavior to get ahead in society. Tina Fey’s quote that if girls call each other sluts, it makes it okay for guys to, basically sums up the main premise of the film: that misogyny is a problem with girls and women, not with men and patriarchy. Don’t get me wrong: internalized misogyny and girl hate are major issues, but what’s odd about this movie is the implication that girl hate magically appears from nowhere. Sure, the movie may serve as a good launching point for having a discussion with young girls about bullying and body image—but on its own, it doesn’t engage in any real feminist critique or break much ground, and it especially fails women marginalized on other axes. Girl-centric, witty, and hyper-quotable, Mean Girls is a fun time and an incredibly well-made movie with a female-written and female-centric script that encourages girls not to tear each other down, but when you analyze it a little deeper or compare it to more feminist comedies like Legally Blonde, its feminism falls short.